By Kavita Nagpal

For the rest of the piece read it here.

The Lost Art of Storytelling

Taal Matol

Dastaan Goee!

By Shoaib Hashmi

Sixty years later, more or less, I can still remember what they looked like. Dark green and printed on cheapish paper they were a series of little booklets called 'Umroo Ayyaar Ki Ayyarian', and there were twenty-five or thirty of the not numbered so someone had to read them and put them in sequence, and an elder cousin had undertaken to read them to us kids, one book each evening after dinner. We did not mind because the whole day was spent loitering about as is the wont of the young, in a dream world populated by self, and Umroo and Amir Hamza and the adventures.

The series has long been out of print which is a great pity because it was the last trace of the hallowed tradition of Dastaan Goee, of story telling! The 'Daastaan-e- Amir Hamza' and its extended version the 'Talism-e-Hosh Ruba' is one of the greatest masterpieces of old style story telling; ostensibly an account of the adventures of Amir Hamza and his friends Umroo or more properly Amru, and Muqbal Vafadaar. They are a fictionalised account of Amir's prowess before the historical times of the Ahd-e-Risalat which gave him his towering reputation as a warrior of legend.

No one, not even the Metropolitan Museum of New York, has been able to trace exactly when or by whom they were first compiled. There are various references that it was by one of the two courtiers of Akbar the Great, Faizee or his brother Abul Fazl, and they might have been collated and compiled by one of them -- because the great 'Hamza Namah' with hundreds of huge and wonderful illustrations was compiled in Akbar's time, and still exists, but the origins of the original concoction of the tale, like all great folk tales is lost in time.

The tale was irresistible and totally compulsive; once you got into it you never got out! Beginning with the near simultaneous birth of Amru and Amir Hamza, it set the tone when the first person who put his finger in Amru's infant mouth to soothe him, lost his ring there; and went on from there. There have been attempts to ascribe it to some other hero named Hamza, but there is no doubt who was meant in the original, and after a myriad adventures taking them to Serenaded and India, the Maldives, they eventually even came circle and ended with Uhud.

But on the way the temptation was great, and everyone who got a chance added his own two bits worth extending it all over, and finally into the magic world of 'Talism-e-Hosh Ruba' full of fairies and Jinns and magicians and sorcerers; and vertically to the children and grandchildren of Amir Hamza and Amru. It grew to forty six large volumes which, thankfully Sang-e-Meel has condensed to thirteen!

The rub is that even in so many volumes the written word gives just the bare gist of the story, and the story teller was required to fill in the details and the dialogue and the colour himself, and captivate his audience with the richness of his narrative -- and this grew into the great tradition of Dastaan Goee. The story teller would travel from village to village keeping the whole populace riveted after dark, when there was nothing else to do, and maybe go on for days or weeks on end as long as the pin money poured in.

One thing was that the people who heard these stories, like us as kids, got lost in the story world and stopped working, and so the word grew that the stories were a 'Nahoosat', a curse and to be avoided. The other was that radio, and film and eventually TV came along, and people learnt to get their thrills otherwise and Dastaan Goee died out.

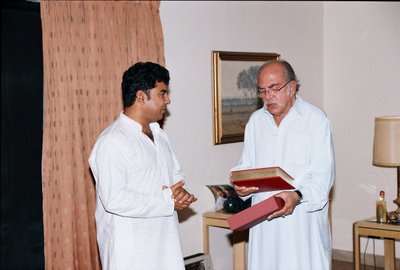

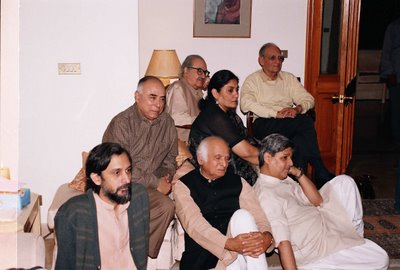

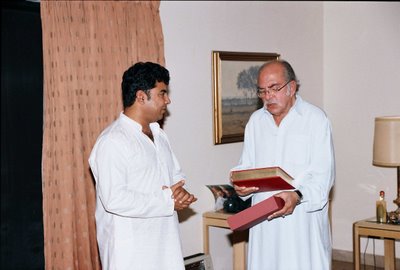

First our friend Shahnaz Aijazuddin got interested and was easily persuaded to try her hand at translating it and making it accessible to a younger generation. And last week a young man, Danish by name came over with the cast of 'Mirza Bagh' which was a great hit at the Festival of Performing Arts. He and a few friends have revived the art form and have been going all over India performing their own creations of the age old tales.

Shahnaz called us over, gave us a sumptuous high tea, and got Danish to perform one of the episodes for a captivated audience. It was a very sweet little evening. One could see how the genre gave the performer almost infinite scope for his own creativity and a vehicle for his gifts. We were told the form is catching the attention more and more in India and beginning to be written about all over.

I do not think the hundred odd TV channels will be quaking in their boots waiting to be swamped under; it will take more than an ancient art form to drag the masses, with their twenty second attention span, and their senses saturated, away from the idiot box to a more civilised way of being entertained, but it could become a nice little niche for a few civilised to occasionally dabble in culture without losing their minds. We hear the redoubtable Naseeruddin Shah may be interested, so they might be on the way!

Almost Island is a web journal of literature, due to appear soon. It is edited by Sharmistha Mohanty, with Vivek Narayanan as contributing editor. To celebrate its founding, Almost Island would like to invite you to a series of readings, Dec-15-17, at 6:30 p.m., at the India International Centre Annexe lawns, Lodhi Institutional Area, Maxmueller Marg, New Delhi.

Dec. 15:

Allen Sealy

Mariko Nagai

K. Satchidanandan

Dec. 16:

Sharmistha Mohanty

Vivek Narayanan

Vinod Kumar Shukla

Dec. 17:

Arvind Krishna Mehrotra

George Szirtes

Followed by

Dastangoi: Revival and Resistance

Periodically in the realm of literary theory the novel is proclaimed dead. The globe is whirling too fast, patience is wearing thin. Contemporary world is seen to have no place for a long narrative that demands silence, cunning, exile for its creation and time, effort, and imagination for its reception. In performing arts the rumour is about the tyranny of the mechanised image; the visual has swallowed the aural. Music unaccompanied by video might soon be relegated to the status of a curiosity. Everywhere there is the demeaning diagnosis of the dumbing down of our sensibilities. We are told that we are living in an age of instant gratification: complexity and slow time are being edged out in favour of mechanization and slickness.

In such a world to revive Dastangoi – traditional Urdu story telling - is clearly an act of courage for which S.R. Faruqi described as ‘the foremost living authority on Dastans and the only person to possess a full set of all the 46 volumes of Dastan-e Amir Humza’ in the IIC brochure and the performers Mahmood Farooqui and Himanshu Tyagi deserve our gratitude and fulsome praise. For one the sheer bulk of the material is intimidating. Farhatullah Baig the writer of ‘The Last Mushairah of Delhi’ is said to have quipped that the combined weight of the volumes would be enough to wreak death upon an unsuspecting reader who dozes off mid-Dastan. Secondly, Dastangoi is a ‘popular’ art form that had the commoners at chauks and nukkads as its aficionados. The Dastangos used to perform at the steps of Jama Masjid. The traditional audiences have melted away into the cinema halls of the cities. At the IIC on 23rd October 2005, as elsewhere, Mahmood Faruqi and Himanshu Tyagi would necessarily perform for a fairly sophisticated audience of bureaucrats and professionals that may be more discerning but suffers the handicap of not possessing the necessary competence in Urdu.

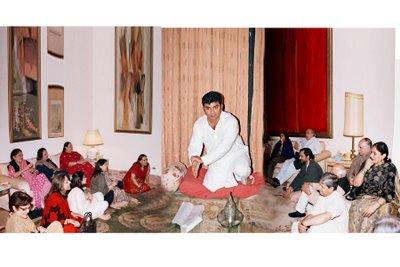

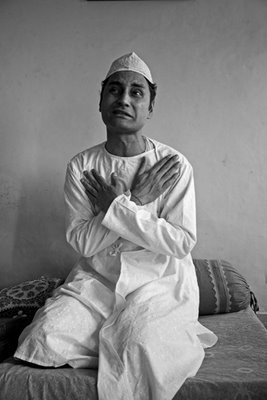

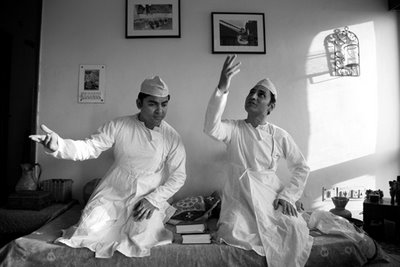

It is to the credit of the conceiver of the show and performers that they neither made allowances for present day audience nor put in any effort to be trendy. The stage was conceived (with input from Habib Tanvir) austerely with a divan in the centre, incense wafting on both sides and the two Dastngos in pure white, seated most of the time, sought to engulf the audience in the pure ‘sea of eloquence’. A glossary of names and recurring words had been circulated but the audience was also advised ‘not to be anxious to understand each and every sentence’. The sense would flow equally from the ambience and the mood. If the performers were not giving leeway they cannot be accused of taking any themselves. In the brochure was an unexpected apology, “The Dastangos of old performed in an oral culture where memory, sound and directness were much prized. As modern actors we neither have the skills to memorise whole daftars, nor the inventiveness to do spontaneous and extempore improvisations which are the hallmark of oral performances.”

With hindsight the apology seems to be a part of the tradition of their performance. The modesty has an old-world feel to it as in their virtuoso performance they did the age they talk about very proud indeed. At least the present reviewer admits to being completely awe-struck by their prodigious memory and wide range of acting. We can safely say that as twenty-first century Dastangos Mahmood Farooqui and Himanshu Tyagi’s act cannot be improved upon.

The selection for the performance was from ‘Tilism-e Hoshruba’, the enchantment cast over the conflict between the righteous Amir Humza, an Uncle of the Prophet and Laqa who falsely claims divinity. It consisted of three whimsical tales of sorcerers, fairies, and tricksters. The tales sought to entertain and please; if there was a moral it certainly wasn’t obtrusive. Amar Aiyar the chief trickster of Laqa foils several attempts made by sorcerers – all of who bear the name ‘Jadu’ – to bring him to book. Magical puppets assume the role of policemen; beautiful women seduce swains with wine; Banias revile the authorities for stealing from them. The world of the Dastan is rich, vivid and staunchly secular.

The audience at the IIC experience seemed to get slightly restless at the end. Perhaps the culprit was the Mughal-Awadhi cuisine that waited. However, the Dastangos – trained over centuries to hold a fickle audience – concluded their amazing performance with aplomb. It was also gratifying to note that a band of admirers hung on every word refusing to be seduced away by coarser pleasures. All in all ‘The Sea of Eloquence – An Evening of Dastan e Amir Hamza’ proved to be a significant effort at revival of a form that had disappeared from the canon of performing arts for almost a century. Its success in present time is heartening not only for its own sake but also for ours. Perhaps some of us along with Farooqui and Tyagi are making an attempt to resist the fast flowing currents of our time.

Anuradha Marwah

By Intizar Hussain

saturday 9th december | |

Dastans are epic narratives and their recitation, including performance and narration, was a “Dastango”. Beginning with a now untraceable, original Arabic version, the story of Hamza, and his exploits against infidels, sorcerers and pretenders to divinity, spread first to the Persian and then to many parts of the Islamic world. |

There was some talk of Danish and his partner Mahmood’s planned visit to Pakistan to present their shows to larger audiences. There is no reason why our own performers cannot take up this challenge. The only one to have recited Urdu poetry and prose on a large scale in Pakistan and abroad is Zia Mohiyyuddin, whose shows are eagerly attended. Such gatherings are invaluable for introducing people to a form of literature that they would not seek out for themselves and for exposing the younger generation to the beauty of the Urdu language. Let us hope that Mahmood Farooqui and Danish Hussain do come to Pakistan in the coming year for it is certain that their shows will have an enthusiastic response here.

There was some talk of Danish and his partner Mahmood’s planned visit to Pakistan to present their shows to larger audiences. There is no reason why our own performers cannot take up this challenge. The only one to have recited Urdu poetry and prose on a large scale in Pakistan and abroad is Zia Mohiyyuddin, whose shows are eagerly attended. Such gatherings are invaluable for introducing people to a form of literature that they would not seek out for themselves and for exposing the younger generation to the beauty of the Urdu language. Let us hope that Mahmood Farooqui and Danish Hussain do come to Pakistan in the coming year for it is certain that their shows will have an enthusiastic response here.

The Dastango constructs a hyper-reality.

The Dastango constructs a hyper-reality.

Stories for fun: Mahmood and Danish at a recording.

Stories for fun: Mahmood and Danish at a recording. Tales of magic and mystery

MITA KAPUR

Mahmood Farooqui and Danish Hussain on their attempt to revive a medieval art of storytelling."Yeh daaru bikau nahin hai," declares a woman. Sorcery, trickery, whoring and wining are a way of life. Mysterious rivers of blood and bridges of smoke flow through visible and invisible realms. Behind veils of darkness, wizards are kings and witches make wine and magic. Amar Aiyaar and Afrasiaab fight battles of wit and Aiyaari is a profession.

Kissas and Kahanis narrated by Mahmood Farooqui and Danish Hussain from Tilsim-e-Hoshruba transport you back in time — to a chowk in Lucknow anywhere between the ninth century and the 20th century.

Dastaangoi (46 volumes) encases the medieval art of storytelling. A dastaango could well be sitting on the steps of Jama Masjid or in a tavern narrating a kissa to an eager audience. You go back to being a child at your grandma's knee, rapt, eager to hear more.

Culture of the court

Strongly Persian in bent, it also used the idioms, language and culture from courtly life in Lucknow. Beginning from the 1880s, Dastaan-e-Amir Hamza was transcribed in Lucknow for about 20 years. Dastaangoi's dastaan slipped into river of silence. Danish felt, "It happened around early 20th century. Dastaangoi has a lot of subversive elements, it poked fun at the Islamic social hierarchy, talked freely about sex, wine, women in the market place, all taboo in Islamic society." According to Mahmood, "It's not simply the story of Dastaangoi, other forms of oral performances also went out of fashion. We can't say that it's because of the conversion from oral to print culture, since a lot of 19th century literary and print culture actually takes off from kissas and kahanis. The decline is inexplicable."

"Dastaans form the backbone of early Parsi theatre and Hindi cinema. There is a recasting of the religious and social order as well. Fantasy has always been considered children's literature. Now these barriers are being broken, it's seeing a revival finally."

Amid all the multi-layers, parallel worlds, fixing the unreal in the real for Mahmood comes with ease. "Dastaangoi is a case of mein kahani suna raha hun, aap baith ke suniye. Though broadly moral, it was written purely to entertain."

Danish (always the villain), explained, "There is no moral theme to these tales. It's not about who is going to win, it's about two sets of extra-witty people trying to outsmart the other. These are tales of good imagination, wholesome and entertaining." Mahmood spoke animatedly, "Dastaans appeal to us today not because they show us the world around us then but because they are fiction at their best. Their world may be far removed but we can still identify with aspects of it."

Likeable villains

"It casts a shadow over Hindi cinema. Gabbar Singh's antecedents are in there. A bloodthirsty character created by a filmmaker and you have Gabbar selling Glucose biscuits! Dastaans also have likeable villains who are still icons for Hindi cinema, although we need reams of study on the linkages. Dastaans are a kind of culmination of many centuries of oral storytelling forms, many structures flow from it."

Society now and the world then, connecting the two, Dan said, "It's all very grey. It's hard to distinguish at times where lies the evil and which side are the righteous people."

Balancing the polarities between Islamic tones and Dastaangoi's shock value, Mahmood said, "How can we typify Dastaangoi as Islamic? The many volumes of Dastaan-e-Amir Hamza were created in Urdu in Lucknow by non-Muslim and Muslim dastaangos. It can't be treated as Islamic literature."

"Among the entire gamut of characters, a minority are Muslim. How does it exactly dovetail with Islamism? Its Persian tones are no longer important in this century. Urdu poetry has diverged from Persian poetry. It is deeply rooted in North Indian poetic realms. Hafiz makes as much sense as does Anand Vardhan or Mir. You can't read Urdu poetry without reading Sanskrit theoreticians."

It's `masala entertainment', Mahmood felt, did not take away from the richness of the art form. "A dastaan has many shades to it. It's not like a finished product, a three-hour film or a novel. Different writers have added varying qualities to it." Dan is simpler, "Any art form is masala entertainment at the end of it. If it wasn't, it wouldn't be appreciated by the audience."

Says Mahmood, "The story of Amar Aiyaar capturing Afrasiaab keeps going on for eight volumes. Every time Afrasiaab sends a magician, he either gets killed or captured. It's an episodic formula on which it keeps building up. It's about constructing a story in which the plot vanishes. All you are left with is the telling of the story."

Favourite characters

As for their favourite character, Mahmood chooses Amar Aiyaar. "He is witty, sharp, flight-footed, basically a harami. Everyone loves to play that kind of a character. I have a sneaking sympathy for Afrasiaab, he keeps getting beaten up."

Dan added, "Aiyaar puts Dennis the Menace in the pale. Burk Firangi, an Englishman, is interesting. He's a trickster and he's lovable. Just as smart as a perfect sidekick should be, not smarter than his boss. An apt political comment on the great legendary sidekicks that our political leaders have."

About King Nausherwan's troubled dream, Mahmood says, "Dreams are unlimited. We need many more dastaangos in many more cities doing it in different styles for Dastaangoi to really take off as an art form. We cannot rise alone, for we can't sift grain from the chaff unless we have a body of work to choose from. That's our fundamental dream. We have 46 volumes.... so sooner or later the world is going to come to us."

http://www.hindu.com/mag/2006

Amar Ayaar decides to kill Aazar Jaadu (Is Haraamzaade ko bhi maarna chahiye)...

Amar Ayaar decides to kill Aazar Jaadu (Is Haraamzaade ko bhi maarna chahiye)... Amar Ayyaar disguised as a sorcerer feigns Mahtaab's loss...

Amar Ayyaar disguised as a sorcerer feigns Mahtaab's loss... Aazar Jaadu about to fall for Kalwaarin...

Aazar Jaadu about to fall for Kalwaarin... An afternoon brimming with Mohammad Husain Jaa's poetry...

An afternoon brimming with Mohammad Husain Jaa's poetry... Afrasiyaab's gaze burns the tree...

Afrasiyaab's gaze burns the tree... Kya Ayyaari Hai...

Kya Ayyaari Hai...

بناهاى آباد گردد خراب

ز باران و از تابش آفتاب

پى افكندم از نظم كاخي بلند

كه از باد و باران نيابد گزند

نميرم از اين پس كه من زندهام

كه تخم سخن را پراكندهام

| THE REAL PAGE 3 | |

| Yarn spinner | ||

| Spinning a fantasy no less magical than the Arabian Nights gives Delhite Danish Husain much to do | ||

| Shirin Abbas | ||

| Lucknow, September 30: Chubby cheeked and cherubic, D(a)anish Husain looks as sweet and tempting as the Danish pastries his name is often mispronounced as. His foray into the art form was accidental, but about a dozen sessions of Dastan Goi later, this former corporate banker, now full-time theatre guy, has made it his mission to revive the art form and build a global audience for Dastan Goi. "It was in March this year that I was approached by Mahmood Faroqui who had originally started Dastan Goi with friend Himanshu Tyagi and was on the look out for a partner. We had only twelve-odd days to prepare as the performance was on March 27. It was a very challenging art form and a dozen-odd shows later, I am so glad I took up the task," says Husain. Another plus is the lack of any moralistic stands in the script. "The story is pure entertainment. Apart from the basic premise that Amir Hamza is the good man, the Prophet's uncle out to destroy the charlatan Afrasiyaab, which exempted them from Islamic decrees, there is ample leverage for the main characters to indulge in all sorts of vices- wine, women, makkari, ayyari, magic, fantasy- hence, its appeal." Language too becomes redundant faced with the perfect mimicry that accompanies the art. Husain talks of an American guest at a Mumbai performance who said he understood the entire story without knowing a word of Urdu. "Yes, it is Urdu at its literary best, with more than a fair sprinkling of Faarsi, but the stories have eloquence and a cadence that appeals to all irrespective of whether or not they understand Urdu. The language, the rhythm, the juxtaposition of ideas, metaphors and words bind you," he explains.

"Everything that you start is accompanied by hurdles. It's never a smooth walk initially. More so with people ready to give a communal flavour to the language, an administration apathetic to the cause and educational system that doesn't give you anything by way of an education. But it is heartening to note that despite all this, the response from the general public is always heartening. I think people are aware of their social and cultural responsibility and the need to protect and preserve these dying art forms is propelling them to get back to their roots and make this one bid to preserve their heritage. After the play in Mumbai I met a few young boys- in jeans cargos, tees- like your average metro teenagers and they asked me where and how they could learn Urdu. It made me feel so good about what I was doing."

| ||

| |

| THE REAL PAGE 3 | |

AADAB Lakhnau!

New winds of a cultural revival waft welcome changes in the city, our correspondent explores the trend

Shirin Abbas

* Another September evening at the city's elite MB Club. The crowds today have gathered to witness an ancient dying art, that of Dastan Goi, brought to the city by Delhi's Mehmud Farooqui and Danish Husain who have been invited to Lucknow by bureaucrat Zohra Chaterjee. The initial intrigue gives way to appreciation as the duo weave an enticing tale full of magic realism and visual imagery drawn purely with words, relating the amazing tale of Amir Hamza and his victories over the evil Afrasiyaab. For over two hours the magic holds the full house spell bound-glued to their chairs, as they experience the full magic of an art that has long been consigned to obscurity. The gentry comprises a fair sprinkling of the city's elite, drawn from all walks of life- former Chief Secretary AP Verma, Begum Hamida Habibullah, Zarine Viccajee and Ruddi Kapur, Pradeep and Rashmi Vaid, Meenakshi and Sudhir Pahwa, Former IPS VN Misra, Salim and Noor Khan again, to name but a few. Many have only a little understanding of chaste Urdu, much less the fair sprinkling of Persian used in the dialogue. But the linguistic obstacles do not limit their appreciation of the art...

… Just three events from one week in the life of Lucknow, but sufficient evidence to surmise that something, something very good, is slowly, silently taking shape in the City of the Nawabs. A slow but gradual conscientiousness emerging from the Lakhnavi gentry towards their cultural and literary heritage and the need for its preservation and appreciation.

Ask Noor Khan, educationist, who attended all three functions, on the trend and she avers, "Lucknow has always seen a flurry of activity take place which intensifies as the weather gets better. As for Amir Naqi Khan, I have been attending his dinners for as far back as I can remember. There has been an intensification of this of late, because I think people are realizing that they have let their past slip through in different ways and it is not only beneficial for them but for others as well to revive these traditions. But I think as far as the government is concerned, it is largely a private effort which sees such events taking place in the city. This sort of thing used to take place in Rita Sinha's time and now I must give credit to Zohra Chaterjee for taking a keen interest in reviving these traditions in Lucknow. On the other part I think publications such as the Indian Express with Tumhari Amrita and others have had a significant role in keeping these traditions alive in the city."

Speaking about her effort, Principal Secretary, Electronics and IT, Zohra Chaterjee says with a smile, "The evening of Dastan Goi made me wish sincerely that I had paid more attention to learning Urdu when my mother had insisted I learn the language. I just got through learning the bare minimal skills. I think it's the flavour of the language that holds immense attraction. I for one was overwhelmed by the public response."

Principal Secretary Handlooms & Textiles, Ravinder Singh, who was co-organiser for the event says, " We had wanted to hold a Dastan Goi session long ago but the last Dastan Goh of Lucknow died a decade back. Then Zohra chanced upon Mehmud Farooqui and Danish Husain in Delhi and we decided to call them over. The response has been terrific. We'd love to do more such events in the future."

If the exchange of SMSes between Zohra and Singh are any indication, it could well mark the beginning of a new cultural platform for more such events. Says Zohra " After the function I sent Ravinder an SMS, 'Great synergy. We must do this again sometime,' and he replied, ‘Definitely. Aadab Lucknow.' That's a nice name for a society aiming at cultural revivalism in Lucknow, she concludes." Let's just say Amen to that!

Outlines of Hamza Nama

The Dastan of Tilism-i-Hoshruba is the continuation of the Dastan-i-Amir Hamza, the adventures of the legendary hero Amir Hamza. Although the Tilism is a narrative complete in itself, it helps to be familiar with the outlines of the earlier Hamza story to which there are frequent references in the text of the Tilism.

According to the Hamza Nama, the legendary Persian monarch Nausherwan had a troubling dream. He consulted his gifted astrologer Vizier Buzurchmeher, who interpreted the dream as indicating that Nausherwan would lose his kingdom to a rival for several years, and that it would be restored to him by a young Arab to be born in Mecca at the auspicious moment of the conjunction of Jupiter and Venus. That child was to be Amir Hamza, which is why Hamza was later known as Sahib-qiran or Lord of the Conjunction.

Nausherwan sends his vizier Buzurchmeher to Mecca (then part of the Persian empire) to identify the baby and to ensure that he is reared as a ward of the Persian court. Hamza’s father is identified in the narrative as Abu Muttalib, the leader of the Hashemite clan. The choice of the name Abul Muttalib who was the grandfather of the Holy Prophet Muhammad was not accidental, for it used him – a real figure – as a corner-stone character into an essentially fictional text.

Hamza grows up to become a warrior of formidable strength and intelligence. Hamza, being blessed, receives gifts that have supernatural powers. He is also given the Great Name (legendary unknown name of God) that prevails over all forms of magic. His childhood friends - the wily trickster Amar and the loyal archer Muqbil - are also blessed with divine gifts and remain his companions during his numerous adventures.

In time, Nausherwan uses Hamza to fight on his behalf, but in his heart he fears him. His Vizier Bakhtak fuels Nausherwan’s insecurities and plots against Hamza. Amar shields Hamza against Bakhtak’s fiendish schemes. Hamza and the beautiful Meher Nigar, daughter to Nausherwan, fall in love and Nausherwan reluctantly consents to the marriage. Just before the wedding Hamza is wounded in battle and rescued by Jinni-king Shahpal’s vizier.

In return for the kindness Hamza promises the Jinni king that he will vanquish the defiant devs who have taken over his kingdom. Hamza is trapped in Koh Kaf (land of Jinni and fairies) for 18 years due to the machinations of the Jinni king’s daughter Aasman Pari who is besotted with him. Eventually, Hamza returns to Persia and marries his beloved Meher Nigar who has loyally waited for him.

The last part of Hamza’s story involves his return to Mecca. Here, the fictional Hamza becomes the real Hamza bin Abu Muttalib, who defends his nephew the Holy Prophet Muhammad against the Kaffirs of Mecca and is subsequently martyred at the Battle of Uhud.

Tilism-i-Hoshruba

Amir Hamza re-appears as a hero in the Tilism-i-Hoshruba. The literal meaning of the word Tilism is enchantment. Hoshruba is an empire of enchantments that contains many other magic-bound realms within it. The Tilisms are deemed to have been created by an ancient pantheon of gods such as Samri, Jamshed, Laat and Manaat who have been long dead but whose magic remains alive through their creations. The realm of Hoshruba itself consists of the Visible and the Invisible Tilisms (divided by the River of Blood) and a mysterious place of the darkest magic best described as the Veil of Darkness. These Tilisms are populated by wizards and witches whose names reflect the kind of magic they practice. Witches are as powerful as wizards; they rule kingdoms; they lead armies, and they are given equal importance in the narrative. .

Tilism-e-Hoshruba recounts the adventures of Amir Hamza and his sons and grandsons - all of them (like their illustrious forebear) brave, chivalrous and stunningly handsome.

The Tilism-dastans usually involve a quest for the Lauh-i-Tilism - the magic tablet or keystone that is closely guarded by the ruler of the Tilism. The keystone is so designed that only the person destined to vanquish the Tilism, known as the Tilism Kusha, is able to reach it. The keystone requires some sort of sacrifice, usually of blood before it reveals its secrets to the Tilism Kusha and guides him.

The story begins with Hamza as the commander-in chief of the Islamic army defeating a Persian ruler Laqa, who has been making false claims to divinity. Amir Hamza chases him out of the Tilism of a Thousand Faces into Kohistan. Laqa takes refuge in Kohistan because it shares a border with the Tilism-i-Hoshruba. The ruler of Hoshruba Afrasiab is the formidable King of Wizards who reveres Laqa and deputes his wizards to help Laqa fight Hamza.

Laqa’s allies include the sons of Naushervan, Hamza’s old patron and adversary from the days of the Dastan-i-Hamza. Laqa’a vizier is Bakhtiarak son of Bakhtak, the vizier who had schemed against Hamza and Amar in the earlier legends.

Hamza’s childhood companion Amar has a pivotal role in the later narrative. Because of his talent for disguises and trickery, Amar is known as king of Ayyari or tricksters. (Ayyari or the art of trickery is a profession with its own costumes, codes and sign language.) He has an army of over a hundred thousand other tricksters who acknowledge him as their leader and teacher. Amar uses divine gifts such as the cloak of invisibility and the magic pouch that contains many worlds to succeed in his tricks.

Hamza’s astrologers are the sons of the great Buzurchmeher, vizier to Nausherwan. At his behest, they cast an astrological chart and inform him that his grandson Asad is the Tilism Kusha of Hoshruba. Hamza sends Asad to invade Hoshruba with a large army. Amar and four other tricksters accompany this army. The invaders are beset by magical snares and enchantments at every step, but due to their superior moral authority and physical prowess, they manage to overcome all these hurdles.

Afrasiab, both the King of all Wizards and the emperor of Hoshruba, sends his lesser functionaries to combat Asad and the five tricksters. Afrasiab’s concern is accentuated when his own niece Mahjabeen falls in love with Asad and elopes with him. His consternation is absolute when Mahjabeen’s grandmother – the powerful sorceress Mahrukh – also defects to Asad’s side. Many powerful wizards of Afrasiab’s camp, disgruntled with their own ruler, join the Tilism Kusha Asad and Mahrukh. At this, Afrasiab sends his own wife Hairat along with his best people to confront the rebels, confident that they will be disposed of easily. Despite that, Afrasiab suffers defeats and humiliations at every turn. Eventually he conjures the deepest and darkest magic at his command but is consistently foiled by the cunning ploys used by Asad’s five tricksters.

Afrasiab however manages to capture Asad and Mahjabeen but finds that he cannot execute Asad as that would go against the constitution of the Tilism written by its ancient creators.

Despite the absence of their leader Asad, the rebels gain increasing strength, culminating in their securing the alliance of Kaukab, the powerful ruler of a neighbouring Tilism.

Once Asad is released, the rebels along with their allies help him in the quest for the Loah or keystone. Afrasiab, now desperate, turns to the ancient wizards surviving from the time the Tilism was created.

Eventually after fourteen years of conflict, the Tilism Kusha Asad kills Afrasiab. The land of enchantments is finally rid of all magical illusions. Hamza restores the throne to the former ruler of Hoshruba who had been deposed by Afrasiab and imprisoned by him. The living god Laqa escapes and is rescued and given refuge by another powerful wizard.

THE HISTORY OF THE TILISM

As the Tilism contains so many characters from the original Dastan of Hamza, it has a strong Persian and Arabian flavour. The Tilism dastans evolved in the days of the later Mughals when the kingdom of Awadh was in a decline. Although many of the idioms, language and culture are recognizably derived from courtly life at Lucknow, the Tilism belongs to a time and a space that is all its own. There are few oblique references to the 1857 War of Independence/Mutiny and the presence of the British. However, there is no direct mention of any specific places or towns, as we know them.

The seven daftars or volumes of Tilism-i-Hoshruba form one continuous narrative of prose, interspersed with poetry. Dastan narration was an intrinsic part of the court ritual. It enjoyed a common appeal that encouraged the narrators to tailor their stories to suit their audience.

In the late nineteenth century, the Naval Kishore Press in Lucknow commissioned dastan- narrators or known as dastan-gohs to compile the primarily oral tradition into written form. These were first published between 1883 and 1905.

My interest in the Tilism began as a child when I came across an abridged edition which I read with an almost insatiable appetite. It was written in highly Persianised Urdu but despite its archaic style the beauty and richness of the language and the sheer magic of the story has captivated me over the years. I realised though that for the Tilism to be appreciated by others, it needed to be translated into English while at the same time, its inordinate length – padded by lengthy often gratuitous passages of purple prose and poetry– had to be edited and re-interpreted into a readily intelligible idiom while retaining the flavour of the original.

Dastangoi—the art of reciting dastans, traditional romantic epics that are related to the 1001 Arabian Nights and Panchatantra—is being revived, says Scherazade Kaikobad.

Many of us in the post-Independence generations may be forgiven for believing that the Indian epic tradition is largely restricted to the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Ever since the nationalist movement and the search for a unitary 'national culture' began, there has been a systematic marginalisation of various cultural forms, including 'dastangoi,' the fine art of reciting 'dastans' or medieval romantic epics.

From the coffee houses of Tehran to Delhi's Jama Masjid, from the Qissah-Khvani Bazaar in Peshawar to the Thursday evening salons of the Urdu poet Ghalib and the courts of the Mughal emperors, from far-flung Bosnia to Indonesia, dastangoi has had a rich tradition, from the ninth century to the turn of the 20th century.

Dastans were derived from a common pool of stories, narrative techniques and literary styles. The Panchatantra, Jataka Tales, 1001 Arabian Nights, Shah Nama and other romances are part of this vast pool, created by the swirling currents of translation.

At the height of its popularity in the late 19th to the early 20th century, the Indian dastan tradition was both an oral performance, as well as a written literary form. A 19th century print version of the Dastan-e-Amir Hamza ran into 46 volumes of about 900 pages each, making it possibly the single longest romance in the world.

The dastan influenced not only Urdu literature, but possibly also Parsi theatre, and through it, Hindi cinema. How is it, then, that this once-thriving form has been virtually obliterated from the popular imagination? That is what Mahmood Farooqui, the Delhi-based columnist, writer and actor, has researched and attempted to redress. Along with co-actor and writer Danish Husain, he is currently treating Mumbai to the lost art of dastangoi. They will perform at Prithvi Theatre on July 1 and 2.

Based on excerpts from the Tilism-e-Hoshruba (the enchantment that steals away the senses), stories from the Dastan-e-Amir Hamza, this modern-day dastangoi strikes a fine balance between narration and dramatisation.

While the stories recount the adventures of Amir Hamza, the selected episodes deal with the enchantment cast by Afrasiyab Jadu, the emperor of sorcerers, and the havoc wrecked by Amar Aiyyar (who is not exactly a Tam Bram, but a trickster).

While it helps to know Urdu, the performance remains accessible and funny. Says Danish Husain, “Apart from dramatic and linguistic skills, dastangoes must improvise as poets.”

Says Mahmood Farooqui, “With its freewheeling fantasy, the dastans' fall from literary favour coincided with a period when Indians were looking to match Dickens' realism. The Indian middle class is influenced by Victorian moral codes, so the humour in dastans was considered vulgar. Dastangoi has always been high-class masala entertainment.”

Dastangoi, Prithvi Theatre, July 1 and 2, 9pm

PS: This article was published in The DNA Newspaper, a Mumbai based newspaper, in the Salon section; edition dated July 01, 2006.