Dastan-go, an extinct breed

By Intizar Hussain

AN invitation from Begum Shahnaz Aijazuddin for a mahfil at her residence, where a dastango was to demonstrate his art of dastangoi came as a surprise to me. The variety of storyteller known as a dastan-go is now an extinct breed. How and where from did she unearth this rare relic?

She has a ready reply for it, “in the back garden of India International Centre of Delhi.” And she explains, “There I was witness to an unusual and dramatic performance. It was an oral narration in the traditional style of dastangoi or kissa khwani, the rare art of storytelling, revived that enchanted evening by two talented young performers, Mahmood Farooqui and Himanshu Tiyagi.”

She further says, “What surprised me was how a modern audience in Delhi, many of whom were hearing the text for the first time, seemed to be equally captivated.”

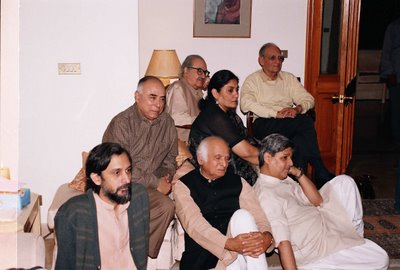

That evening in IIC brought the magic of Tilism back to life for her. Enamoured of that evening she returned to life. She did not have to wait for long. Last week, a partner of Mahmood Farooqui arrived here from Delhi. She hurriedly arranged at her residence an evening of dastangoi in his honour. She invited her close friends hoping that they will share her experience and will enjoy that peculiar art of storytelling, which is now lost to us.

A number of intellectuals, mostly ladies, had gathered at her residence with a curiosity for this forgotten traditional art. For the benefit of this select audience Begum Shahnaz talked briefly about Tailism-e-Hoshruba explaining what kind of fiction it is. In fact, she herself has a deep involvement in this dastan, which runs in eight big volumes. As she wrote in an article, she begun reading it at the age of ten. From then till now she has been under its spell. She has written about it and is for long engaged in translating it in English.

She then introduced to the audience her guests, who had come from Delhi. A young man clad in white kurta pajama made his appearance and sat on the masnad with a gao-takiya on his back. He was dastango Danish Husain. Originally, he is a man of theatre. But now he has also accomplished himself in the art of dastangoi and acts as a partner of Mahmood Farooqui, who, as he informed us, is the maternal nephew of Shamsurrahman Farooqui. And, as is known, Shamsurrahman as a scholar has dived in all the 46 bulky volumes of Dastan-e-Amir Hamza.

Danish Husain had only one request to make to his audience: no clapping please. He was right. A dastan can hardly reconcile with this modern way of applause. He rather expected applause through the traditional expressions of “Wah, wah” and “SubhanAllah”. But the modern audience has its own preferences and prejudices. It cannot afford to reconcile with “Wah, wah” and “SubhanAllah”. So a gentle laughter was deemed fit to be utilized as an alternative way of applause.

The devoted souls trying to revive dastangoi may or may not succeed in their mission, but it at least is a sign of a revival of interest in our lost art forms. This revival of interest perhaps carries with it a sense of great loss. The lost art of dastangoi reminds us of times when our fiction had the backing of a well-developed oral tradition ranging from the steps of Delhi’s Shahjehani Masjid to the Diwankhanas of the elites. But as times changed and new social and literary movements made their appearance, the whole tradition of dastan and dastangoi came under heavy attack and was condemned as something decadent and reactionary.

Of course dastan still enjoyed popularity in the face of newly borrowed forms of fiction, short story and novel, but its decline had set in. The worst sufferer was dastango. He was no more in demand the way he was in days gone by. He now appeared to be a vanishing breed. The last distinguished dastango one can trace in the history of Urdu dastan was Mir Baqar Ali of Delhi. His gradual fall from grace tells the sad story of the decline and degradation of this institution. At one time he was in great demand; so much so that he could afford to reject the offers made by the nawabs and rajas eager to engage him.

He went to Patiala accepting the maharaja’s offer for his association with his court. But when he was told that he had to appear in his court with a turban on his head, he refused to observe this condition and was ready to go back to his city. The maharaja readily relaxed this condition and he appeared in his court with the traditional cap he usually had on his head.

In later years he was patronized by the gentry of Delhi, especially by Hakim Ajmal Khan. When invited, he appeared in his diwan khana and narrated dastan to the select audience there.

But times changed rapidly. He lost all his patrons for one reason or the other. Now he was obliged to hold mahfil at his own residence charging one anna per head from his audience.

This too did not last long. The city of Delhi was under the sway of a new wonder known as bioscope. Those few listeners too left him and rushed to the cinema houses. He was now left with no choice but to say goodbye to the art that was so dear to him.

In his last days Mir Baqar had turned a vendor, selling betel nuts. When asked about his newly adopted business, he promptly replied “Dillewallas have forgotten the fine manners of chewing pans. Main unhain pan khanay kay adaab sikharaha hoon.”

This was the way the charming tradition of Dastangoi came to an end.

PS: This article was published in Dawn, Pakistan on December 03, 2006.

http://www.dawn.com/weekly/dmag/dmag13.htm

She has a ready reply for it, “in the back garden of India International Centre of Delhi.” And she explains, “There I was witness to an unusual and dramatic performance. It was an oral narration in the traditional style of dastangoi or kissa khwani, the rare art of storytelling, revived that enchanted evening by two talented young performers, Mahmood Farooqui and Himanshu Tiyagi.”

She further says, “What surprised me was how a modern audience in Delhi, many of whom were hearing the text for the first time, seemed to be equally captivated.”

That evening in IIC brought the magic of Tilism back to life for her. Enamoured of that evening she returned to life. She did not have to wait for long. Last week, a partner of Mahmood Farooqui arrived here from Delhi. She hurriedly arranged at her residence an evening of dastangoi in his honour. She invited her close friends hoping that they will share her experience and will enjoy that peculiar art of storytelling, which is now lost to us.

A number of intellectuals, mostly ladies, had gathered at her residence with a curiosity for this forgotten traditional art. For the benefit of this select audience Begum Shahnaz talked briefly about Tailism-e-Hoshruba explaining what kind of fiction it is. In fact, she herself has a deep involvement in this dastan, which runs in eight big volumes. As she wrote in an article, she begun reading it at the age of ten. From then till now she has been under its spell. She has written about it and is for long engaged in translating it in English.

She then introduced to the audience her guests, who had come from Delhi. A young man clad in white kurta pajama made his appearance and sat on the masnad with a gao-takiya on his back. He was dastango Danish Husain. Originally, he is a man of theatre. But now he has also accomplished himself in the art of dastangoi and acts as a partner of Mahmood Farooqui, who, as he informed us, is the maternal nephew of Shamsurrahman Farooqui. And, as is known, Shamsurrahman as a scholar has dived in all the 46 bulky volumes of Dastan-e-Amir Hamza.

Danish Husain had only one request to make to his audience: no clapping please. He was right. A dastan can hardly reconcile with this modern way of applause. He rather expected applause through the traditional expressions of “Wah, wah” and “SubhanAllah”. But the modern audience has its own preferences and prejudices. It cannot afford to reconcile with “Wah, wah” and “SubhanAllah”. So a gentle laughter was deemed fit to be utilized as an alternative way of applause.

The devoted souls trying to revive dastangoi may or may not succeed in their mission, but it at least is a sign of a revival of interest in our lost art forms. This revival of interest perhaps carries with it a sense of great loss. The lost art of dastangoi reminds us of times when our fiction had the backing of a well-developed oral tradition ranging from the steps of Delhi’s Shahjehani Masjid to the Diwankhanas of the elites. But as times changed and new social and literary movements made their appearance, the whole tradition of dastan and dastangoi came under heavy attack and was condemned as something decadent and reactionary.

Of course dastan still enjoyed popularity in the face of newly borrowed forms of fiction, short story and novel, but its decline had set in. The worst sufferer was dastango. He was no more in demand the way he was in days gone by. He now appeared to be a vanishing breed. The last distinguished dastango one can trace in the history of Urdu dastan was Mir Baqar Ali of Delhi. His gradual fall from grace tells the sad story of the decline and degradation of this institution. At one time he was in great demand; so much so that he could afford to reject the offers made by the nawabs and rajas eager to engage him.

He went to Patiala accepting the maharaja’s offer for his association with his court. But when he was told that he had to appear in his court with a turban on his head, he refused to observe this condition and was ready to go back to his city. The maharaja readily relaxed this condition and he appeared in his court with the traditional cap he usually had on his head.

In later years he was patronized by the gentry of Delhi, especially by Hakim Ajmal Khan. When invited, he appeared in his diwan khana and narrated dastan to the select audience there.

But times changed rapidly. He lost all his patrons for one reason or the other. Now he was obliged to hold mahfil at his own residence charging one anna per head from his audience.

This too did not last long. The city of Delhi was under the sway of a new wonder known as bioscope. Those few listeners too left him and rushed to the cinema houses. He was now left with no choice but to say goodbye to the art that was so dear to him.

In his last days Mir Baqar had turned a vendor, selling betel nuts. When asked about his newly adopted business, he promptly replied “Dillewallas have forgotten the fine manners of chewing pans. Main unhain pan khanay kay adaab sikharaha hoon.”

This was the way the charming tradition of Dastangoi came to an end.

PS: This article was published in Dawn, Pakistan on December 03, 2006.

http://www.dawn.com/weekly/dmag/dmag13.htm

No comments:

Post a Comment