By Kavita Nagpal

For the rest of the piece read it here.

The Lost Art of Storytelling

Taal Matol

Dastaan Goee!

By Shoaib Hashmi

Sixty years later, more or less, I can still remember what they looked like. Dark green and printed on cheapish paper they were a series of little booklets called 'Umroo Ayyaar Ki Ayyarian', and there were twenty-five or thirty of the not numbered so someone had to read them and put them in sequence, and an elder cousin had undertaken to read them to us kids, one book each evening after dinner. We did not mind because the whole day was spent loitering about as is the wont of the young, in a dream world populated by self, and Umroo and Amir Hamza and the adventures.

The series has long been out of print which is a great pity because it was the last trace of the hallowed tradition of Dastaan Goee, of story telling! The 'Daastaan-e- Amir Hamza' and its extended version the 'Talism-e-Hosh Ruba' is one of the greatest masterpieces of old style story telling; ostensibly an account of the adventures of Amir Hamza and his friends Umroo or more properly Amru, and Muqbal Vafadaar. They are a fictionalised account of Amir's prowess before the historical times of the Ahd-e-Risalat which gave him his towering reputation as a warrior of legend.

No one, not even the Metropolitan Museum of New York, has been able to trace exactly when or by whom they were first compiled. There are various references that it was by one of the two courtiers of Akbar the Great, Faizee or his brother Abul Fazl, and they might have been collated and compiled by one of them -- because the great 'Hamza Namah' with hundreds of huge and wonderful illustrations was compiled in Akbar's time, and still exists, but the origins of the original concoction of the tale, like all great folk tales is lost in time.

The tale was irresistible and totally compulsive; once you got into it you never got out! Beginning with the near simultaneous birth of Amru and Amir Hamza, it set the tone when the first person who put his finger in Amru's infant mouth to soothe him, lost his ring there; and went on from there. There have been attempts to ascribe it to some other hero named Hamza, but there is no doubt who was meant in the original, and after a myriad adventures taking them to Serenaded and India, the Maldives, they eventually even came circle and ended with Uhud.

But on the way the temptation was great, and everyone who got a chance added his own two bits worth extending it all over, and finally into the magic world of 'Talism-e-Hosh Ruba' full of fairies and Jinns and magicians and sorcerers; and vertically to the children and grandchildren of Amir Hamza and Amru. It grew to forty six large volumes which, thankfully Sang-e-Meel has condensed to thirteen!

The rub is that even in so many volumes the written word gives just the bare gist of the story, and the story teller was required to fill in the details and the dialogue and the colour himself, and captivate his audience with the richness of his narrative -- and this grew into the great tradition of Dastaan Goee. The story teller would travel from village to village keeping the whole populace riveted after dark, when there was nothing else to do, and maybe go on for days or weeks on end as long as the pin money poured in.

One thing was that the people who heard these stories, like us as kids, got lost in the story world and stopped working, and so the word grew that the stories were a 'Nahoosat', a curse and to be avoided. The other was that radio, and film and eventually TV came along, and people learnt to get their thrills otherwise and Dastaan Goee died out.

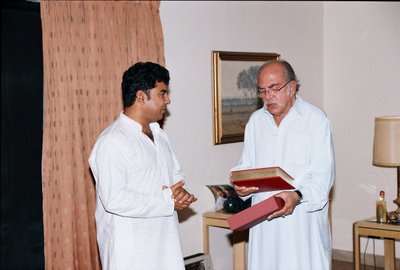

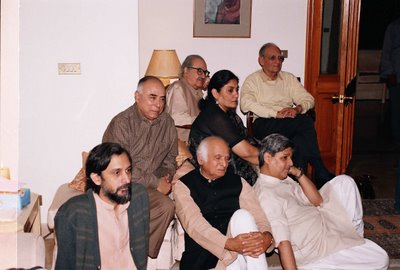

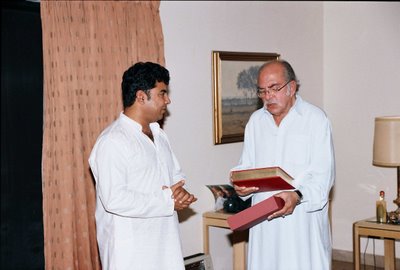

First our friend Shahnaz Aijazuddin got interested and was easily persuaded to try her hand at translating it and making it accessible to a younger generation. And last week a young man, Danish by name came over with the cast of 'Mirza Bagh' which was a great hit at the Festival of Performing Arts. He and a few friends have revived the art form and have been going all over India performing their own creations of the age old tales.

Shahnaz called us over, gave us a sumptuous high tea, and got Danish to perform one of the episodes for a captivated audience. It was a very sweet little evening. One could see how the genre gave the performer almost infinite scope for his own creativity and a vehicle for his gifts. We were told the form is catching the attention more and more in India and beginning to be written about all over.

I do not think the hundred odd TV channels will be quaking in their boots waiting to be swamped under; it will take more than an ancient art form to drag the masses, with their twenty second attention span, and their senses saturated, away from the idiot box to a more civilised way of being entertained, but it could become a nice little niche for a few civilised to occasionally dabble in culture without losing their minds. We hear the redoubtable Naseeruddin Shah may be interested, so they might be on the way!

Almost Island is a web journal of literature, due to appear soon. It is edited by Sharmistha Mohanty, with Vivek Narayanan as contributing editor. To celebrate its founding, Almost Island would like to invite you to a series of readings, Dec-15-17, at 6:30 p.m., at the India International Centre Annexe lawns, Lodhi Institutional Area, Maxmueller Marg, New Delhi.

Dec. 15:

Allen Sealy

Mariko Nagai

K. Satchidanandan

Dec. 16:

Sharmistha Mohanty

Vivek Narayanan

Vinod Kumar Shukla

Dec. 17:

Arvind Krishna Mehrotra

George Szirtes

Followed by

Dastangoi: Revival and Resistance

Periodically in the realm of literary theory the novel is proclaimed dead. The globe is whirling too fast, patience is wearing thin. Contemporary world is seen to have no place for a long narrative that demands silence, cunning, exile for its creation and time, effort, and imagination for its reception. In performing arts the rumour is about the tyranny of the mechanised image; the visual has swallowed the aural. Music unaccompanied by video might soon be relegated to the status of a curiosity. Everywhere there is the demeaning diagnosis of the dumbing down of our sensibilities. We are told that we are living in an age of instant gratification: complexity and slow time are being edged out in favour of mechanization and slickness.

In such a world to revive Dastangoi – traditional Urdu story telling - is clearly an act of courage for which S.R. Faruqi described as ‘the foremost living authority on Dastans and the only person to possess a full set of all the 46 volumes of Dastan-e Amir Humza’ in the IIC brochure and the performers Mahmood Farooqui and Himanshu Tyagi deserve our gratitude and fulsome praise. For one the sheer bulk of the material is intimidating. Farhatullah Baig the writer of ‘The Last Mushairah of Delhi’ is said to have quipped that the combined weight of the volumes would be enough to wreak death upon an unsuspecting reader who dozes off mid-Dastan. Secondly, Dastangoi is a ‘popular’ art form that had the commoners at chauks and nukkads as its aficionados. The Dastangos used to perform at the steps of Jama Masjid. The traditional audiences have melted away into the cinema halls of the cities. At the IIC on 23rd October 2005, as elsewhere, Mahmood Faruqi and Himanshu Tyagi would necessarily perform for a fairly sophisticated audience of bureaucrats and professionals that may be more discerning but suffers the handicap of not possessing the necessary competence in Urdu.

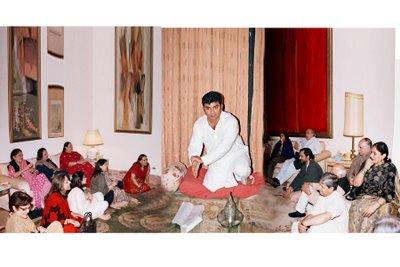

It is to the credit of the conceiver of the show and performers that they neither made allowances for present day audience nor put in any effort to be trendy. The stage was conceived (with input from Habib Tanvir) austerely with a divan in the centre, incense wafting on both sides and the two Dastngos in pure white, seated most of the time, sought to engulf the audience in the pure ‘sea of eloquence’. A glossary of names and recurring words had been circulated but the audience was also advised ‘not to be anxious to understand each and every sentence’. The sense would flow equally from the ambience and the mood. If the performers were not giving leeway they cannot be accused of taking any themselves. In the brochure was an unexpected apology, “The Dastangos of old performed in an oral culture where memory, sound and directness were much prized. As modern actors we neither have the skills to memorise whole daftars, nor the inventiveness to do spontaneous and extempore improvisations which are the hallmark of oral performances.”

With hindsight the apology seems to be a part of the tradition of their performance. The modesty has an old-world feel to it as in their virtuoso performance they did the age they talk about very proud indeed. At least the present reviewer admits to being completely awe-struck by their prodigious memory and wide range of acting. We can safely say that as twenty-first century Dastangos Mahmood Farooqui and Himanshu Tyagi’s act cannot be improved upon.

The selection for the performance was from ‘Tilism-e Hoshruba’, the enchantment cast over the conflict between the righteous Amir Humza, an Uncle of the Prophet and Laqa who falsely claims divinity. It consisted of three whimsical tales of sorcerers, fairies, and tricksters. The tales sought to entertain and please; if there was a moral it certainly wasn’t obtrusive. Amar Aiyar the chief trickster of Laqa foils several attempts made by sorcerers – all of who bear the name ‘Jadu’ – to bring him to book. Magical puppets assume the role of policemen; beautiful women seduce swains with wine; Banias revile the authorities for stealing from them. The world of the Dastan is rich, vivid and staunchly secular.

The audience at the IIC experience seemed to get slightly restless at the end. Perhaps the culprit was the Mughal-Awadhi cuisine that waited. However, the Dastangos – trained over centuries to hold a fickle audience – concluded their amazing performance with aplomb. It was also gratifying to note that a band of admirers hung on every word refusing to be seduced away by coarser pleasures. All in all ‘The Sea of Eloquence – An Evening of Dastan e Amir Hamza’ proved to be a significant effort at revival of a form that had disappeared from the canon of performing arts for almost a century. Its success in present time is heartening not only for its own sake but also for ours. Perhaps some of us along with Farooqui and Tyagi are making an attempt to resist the fast flowing currents of our time.

Anuradha Marwah

By Intizar Hussain

saturday 9th december | |

Dastans are epic narratives and their recitation, including performance and narration, was a “Dastango”. Beginning with a now untraceable, original Arabic version, the story of Hamza, and his exploits against infidels, sorcerers and pretenders to divinity, spread first to the Persian and then to many parts of the Islamic world. |

There was some talk of Danish and his partner Mahmood’s planned visit to Pakistan to present their shows to larger audiences. There is no reason why our own performers cannot take up this challenge. The only one to have recited Urdu poetry and prose on a large scale in Pakistan and abroad is Zia Mohiyyuddin, whose shows are eagerly attended. Such gatherings are invaluable for introducing people to a form of literature that they would not seek out for themselves and for exposing the younger generation to the beauty of the Urdu language. Let us hope that Mahmood Farooqui and Danish Hussain do come to Pakistan in the coming year for it is certain that their shows will have an enthusiastic response here.

There was some talk of Danish and his partner Mahmood’s planned visit to Pakistan to present their shows to larger audiences. There is no reason why our own performers cannot take up this challenge. The only one to have recited Urdu poetry and prose on a large scale in Pakistan and abroad is Zia Mohiyyuddin, whose shows are eagerly attended. Such gatherings are invaluable for introducing people to a form of literature that they would not seek out for themselves and for exposing the younger generation to the beauty of the Urdu language. Let us hope that Mahmood Farooqui and Danish Hussain do come to Pakistan in the coming year for it is certain that their shows will have an enthusiastic response here.

The Dastango constructs a hyper-reality.

The Dastango constructs a hyper-reality.

Stories for fun: Mahmood and Danish at a recording.

Stories for fun: Mahmood and Danish at a recording. Tales of magic and mystery

MITA KAPUR

Mahmood Farooqui and Danish Hussain on their attempt to revive a medieval art of storytelling."Yeh daaru bikau nahin hai," declares a woman. Sorcery, trickery, whoring and wining are a way of life. Mysterious rivers of blood and bridges of smoke flow through visible and invisible realms. Behind veils of darkness, wizards are kings and witches make wine and magic. Amar Aiyaar and Afrasiaab fight battles of wit and Aiyaari is a profession.

Kissas and Kahanis narrated by Mahmood Farooqui and Danish Hussain from Tilsim-e-Hoshruba transport you back in time — to a chowk in Lucknow anywhere between the ninth century and the 20th century.

Dastaangoi (46 volumes) encases the medieval art of storytelling. A dastaango could well be sitting on the steps of Jama Masjid or in a tavern narrating a kissa to an eager audience. You go back to being a child at your grandma's knee, rapt, eager to hear more.

Culture of the court

Strongly Persian in bent, it also used the idioms, language and culture from courtly life in Lucknow. Beginning from the 1880s, Dastaan-e-Amir Hamza was transcribed in Lucknow for about 20 years. Dastaangoi's dastaan slipped into river of silence. Danish felt, "It happened around early 20th century. Dastaangoi has a lot of subversive elements, it poked fun at the Islamic social hierarchy, talked freely about sex, wine, women in the market place, all taboo in Islamic society." According to Mahmood, "It's not simply the story of Dastaangoi, other forms of oral performances also went out of fashion. We can't say that it's because of the conversion from oral to print culture, since a lot of 19th century literary and print culture actually takes off from kissas and kahanis. The decline is inexplicable."

"Dastaans form the backbone of early Parsi theatre and Hindi cinema. There is a recasting of the religious and social order as well. Fantasy has always been considered children's literature. Now these barriers are being broken, it's seeing a revival finally."

Amid all the multi-layers, parallel worlds, fixing the unreal in the real for Mahmood comes with ease. "Dastaangoi is a case of mein kahani suna raha hun, aap baith ke suniye. Though broadly moral, it was written purely to entertain."

Danish (always the villain), explained, "There is no moral theme to these tales. It's not about who is going to win, it's about two sets of extra-witty people trying to outsmart the other. These are tales of good imagination, wholesome and entertaining." Mahmood spoke animatedly, "Dastaans appeal to us today not because they show us the world around us then but because they are fiction at their best. Their world may be far removed but we can still identify with aspects of it."

Likeable villains

"It casts a shadow over Hindi cinema. Gabbar Singh's antecedents are in there. A bloodthirsty character created by a filmmaker and you have Gabbar selling Glucose biscuits! Dastaans also have likeable villains who are still icons for Hindi cinema, although we need reams of study on the linkages. Dastaans are a kind of culmination of many centuries of oral storytelling forms, many structures flow from it."

Society now and the world then, connecting the two, Dan said, "It's all very grey. It's hard to distinguish at times where lies the evil and which side are the righteous people."

Balancing the polarities between Islamic tones and Dastaangoi's shock value, Mahmood said, "How can we typify Dastaangoi as Islamic? The many volumes of Dastaan-e-Amir Hamza were created in Urdu in Lucknow by non-Muslim and Muslim dastaangos. It can't be treated as Islamic literature."

"Among the entire gamut of characters, a minority are Muslim. How does it exactly dovetail with Islamism? Its Persian tones are no longer important in this century. Urdu poetry has diverged from Persian poetry. It is deeply rooted in North Indian poetic realms. Hafiz makes as much sense as does Anand Vardhan or Mir. You can't read Urdu poetry without reading Sanskrit theoreticians."

It's `masala entertainment', Mahmood felt, did not take away from the richness of the art form. "A dastaan has many shades to it. It's not like a finished product, a three-hour film or a novel. Different writers have added varying qualities to it." Dan is simpler, "Any art form is masala entertainment at the end of it. If it wasn't, it wouldn't be appreciated by the audience."

Says Mahmood, "The story of Amar Aiyaar capturing Afrasiaab keeps going on for eight volumes. Every time Afrasiaab sends a magician, he either gets killed or captured. It's an episodic formula on which it keeps building up. It's about constructing a story in which the plot vanishes. All you are left with is the telling of the story."

Favourite characters

As for their favourite character, Mahmood chooses Amar Aiyaar. "He is witty, sharp, flight-footed, basically a harami. Everyone loves to play that kind of a character. I have a sneaking sympathy for Afrasiaab, he keeps getting beaten up."

Dan added, "Aiyaar puts Dennis the Menace in the pale. Burk Firangi, an Englishman, is interesting. He's a trickster and he's lovable. Just as smart as a perfect sidekick should be, not smarter than his boss. An apt political comment on the great legendary sidekicks that our political leaders have."

About King Nausherwan's troubled dream, Mahmood says, "Dreams are unlimited. We need many more dastaangos in many more cities doing it in different styles for Dastaangoi to really take off as an art form. We cannot rise alone, for we can't sift grain from the chaff unless we have a body of work to choose from. That's our fundamental dream. We have 46 volumes.... so sooner or later the world is going to come to us."

http://www.hindu.com/mag/2006